NCAI VOTE TO EXCLUDE STATE RECOGNIZED NATIONS FAILS

November 19, 2023

NCAI vote to exclude state recognized nations fails – ICT News

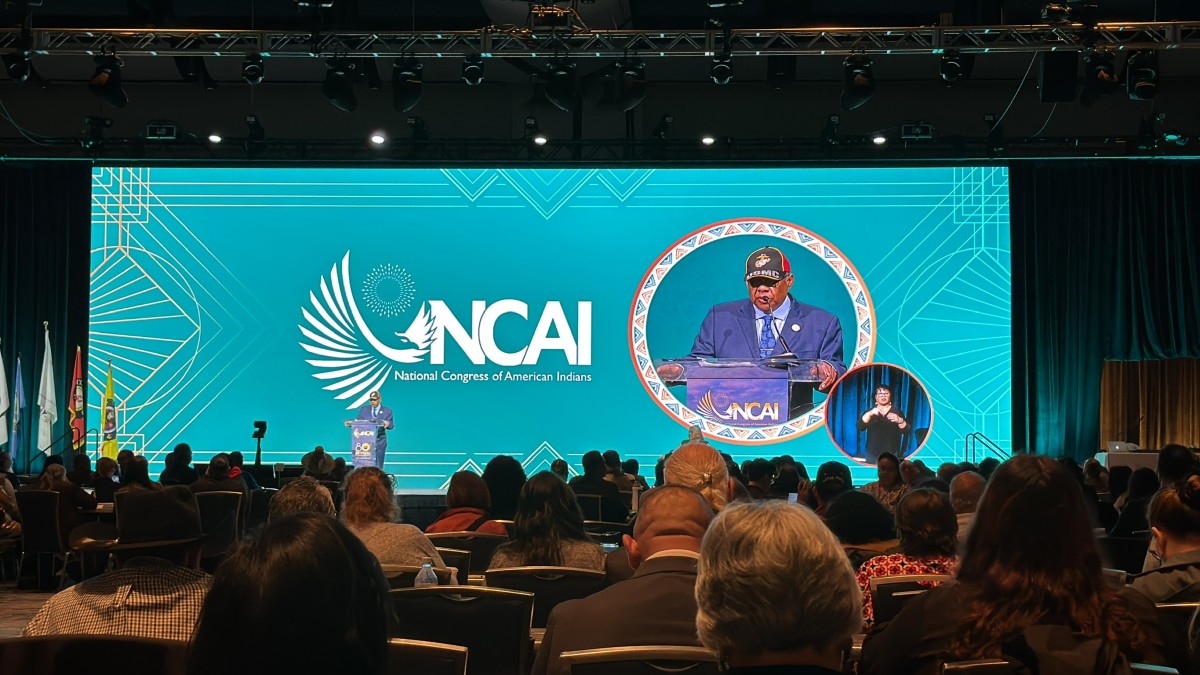

During a contentious week at the 80th annual National Congress of American Indians conference, members took a vote on two constitutional amendments that would exclude state-recognized nations from voting membership. Both proposed constitutional amendments failed.

If the amendments had passed, state-recognized nations could still be members of NCAI, but they would not be able to vote on important issues, such as presidential elections.

In the election Thursday morning, both proposed constitutional amendments failed — a win for the 24 tribes who would have been automatically excluded from voting membership if the amendment had succeeded.

Proposal one: to amend NCAI to limit membership to federally recognized tribes was rejected, with 55.67 percent against and 44.3 percent of voters in favor, according to real time reporting by indianz.

Proposal two: to amend NCAI to limit individual membership and leadership positions to citizens of federally recognized tribes was also rejected with 56.1 percent against and 43 percent of voters in favor, according to real time reporting by indianz.

At least two-thirds of the votes were needed in order for the proposed amendments to pass. Also on Thursday, members elected Mark Macarro, chairman of the Pechanga Band of Indians, as NCAI’s newest president elect.

For the principal chief of the tribal nation whose homelands the meeting is taking place on, the outcome of the vote was especially meaningful.

“We were thrilled when we learned that NCAI would be held here in New Orleans — couldn’t wait to share our rich culture, food, music and traditions with you,” said Lora Ann Chaisson, principal chief of the United Houma Nation, during the deliberation period on Tuesday. “Imagine my shock and surprise and sadness when I learned that tribes from miles away are coming to our ancestral homelands to tell us, the United Houma Nation, a host tribe, that not only are we not a tribe, but that we are not even Indian people.”

The amendments

The first proposed amendment, sponsored by the Eastern Band of Cherokee and the Shawnee Tribe, would require all member nations to be included on the annual list published in the Federal Register, as specified under the Federally Recognized Tribes List Act in order to be eligible for voting membership. It specifies that state-recognized nations would be eligible for membership, but would not have the ability to vote.

The second proposed amendment, sponsored by the Ute Indian Tribe, would require all individual members to be members of a nation included on the list of federally recognized Native nations to be eligible for voting membership. It would also mean that to qualify for an official nomination, an individual must be part of a federally recognized nation.

State versus federal recognition — what does it mean?

Sovereignty is not determined or bestowed by the U.S. government. Tribal nations determine their own sovereignty — and that has existed for each tribe since time immemorial. However, the federal government determines federal recognition of a tribal nation’s sovereign status – through a byzantine process that excludes some.

To date, there are 574 federally recognized Native nations. As of 2019, there were 66 state recognized Native nations across 13 states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

For the 574 federally recognized nations, this means the federal government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, has recognized their sovereign rights to govern themselves and engage in government-to-government relations with the United States government, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs website.

Gaining federal recognition is a complicated process. The federal government — which attempted to ethnically cleanse these nations through genocide and assimilation — requires that each nation “prove” to be who they say they are by providing documentation, largely from non-Native historians because many nations relied on oral histories. Relocation also impacted many nation’s ability to document and prove that they have remained a nation, despite every effort by the federal government to assimilate them.

In the 1700s and 1800s, federal recognition was achieved through treaties with the U.S. government. In 1934, the U.S. government passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which encouraged tribal nations to set up governments molded in the image of the federal government and required federal government approval of tribal constitutions.

Starting in the late 1970s, the Department of Interior issued the Federal Acknowledgement Process, which outlined a process to handle requests for federal recognition. In the 1990s, Congress enacted the Federally Recognized Indian Tribes List Act — which established the list that proponents of the proposed NCAI constitutional amendments would like to rely on to dictate voting membership eligibility.

The federal government has outlined three pathways for federal recognition: tribes can become federally recognized by Congress, by administrative procedures under the Federal Acknowledegment Process or by a U.S. Supreme Court decision. Nations previously “terminated” by the federal government may only be restored by Congress.

From 1953 to 1964, the federal government set out on a rampage of detrimental termination policies — the intent was to assimilate Native Americans into “mainstream” society. Termination ended federal recognition of 109 nations across the U.S.

Today, some of the “terminated” nations are now state recognized.

State recognition is granted by state legislatures, which benefits these nations by acknowledging their histories and cultures. State tribal recognition acknowledges a Native nation’s existence within a certain state, but does not guarantee any services. State recognized tribes are not eligible for the basic services promised in treaties that the federal government is obligated to provide in exchange for the land that is today called the United States, such as federal funding and Indian Health Services.

The lead up

In the days leading up to the historic vote, a handful of tribal leaders from nations across the country have issued public statements through social media, and published as opinion pieces in various news organizations.

In a piece published in ICT written by Robert Willams Jr., Lumbee, said he believes supporters of the proposed amendments are furthering colonization. He pointed to the founding principles of NCAI which state: “NCAI was established in 1944 in response to the termination and assimilation policies the US government forced upon tribal governments in contradiction of their treaty rights and status as sovereign nations. To this day, protecting these inherent and legal rights remains the primary focus of NCAI.”

Those principals align with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Williams claims the amendments are directly in opposition both NCAI’s founding principles and UNDRIP.

“But as NCAI heads into its annual meeting highlighting its 80 years of existence, the organization seems to be forgetting its origin, mission, and purpose,” Williams wrote. “The organization that educates about the perils of assimilation and termination is now poised to support – and lead – the eradication of state-recognized tribes.”

In a joint guest opinion piece published in Native News Online, Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe, and Michele Hicks, principal chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, urged NCAI members to vote “yes” on the proposed amendments.

In the piece, Barnes and Hicks write about their concerns regarding “fake tribes.” They argue passing these amendments would help with the alleged issue.

Scroll to Continue

Read More

Who is running for NCAI leadership?

Elizabeth Hoover apologizes for false Indigenous identity

“Under the current NCAI Constitution, ‘tribes’ proven to have no Native ancestry have the same voice and voting power as those tribes who have existed since time immemorial,” the pair wrote. “The proposed amendments would ensure only groups included on the Federally Recognized Indian Tribe List Act would have the ability to vote in the organization.”

Conversations about the proposed amendments continued at the annual NCAI convention itself.

On Tuesday, NCAI members took to the stage to speak either for or against the proposed amendments.

According to sources on the ground, more tribal leaders spoke out in opposition to the proposed amendments than those in support.

“A vote in favor of this amendment is a vote in favor of tearing each other down,” Chaisson said during a speech on Tuesday. “Tribes who are disparaging other tribes are taking a page straight out of colonialism. This is a white man’s way of doing things and it’s not right.”

Tribal leaders from both state- and federally recognized nations spoke up in opposition to the proposed amendments.

Frank Ettawageshik, former chairman of Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and current executive director at United Tribes of Michigan, mentioned in his speech how he was once chairman of a nation during its fight for federal recognition.

“When NCAI was formed, there were not federally recognized tribes and state-recognized tribes. There were Indians,” Ettawageshik said in his speech. “And we all were fighting together, we all were working together. This system that has come into place since then is one that is working to divide us.”

Speaking in support of the proposed amendments was Ute Indian Tribe Chairman Julius Murray.

“We are federally recognized for a reason,” he told the assembly. “We fought these wars while you guys sat on the sideline and waited for the dust to settle, for you guys to come out of the woodworks to start being Indians.”

In a video shared on Twitter, the crowd erupts in boos following this line.

“Well, get some federal recognition,” Murray responds. “There’s a process.”

According to reports from sources on the ground, the speeches during the deliberations led to high emotions and even physical altercations in the hallway.

NCAI’s new president

Also on the table at this week’s annual meeting was the election of a new NCAI president. On Thursday, with 50.31 percent of the vote, Mark Macarro, chairman of the Pechanga Band of Indians became the newest NCAI president elect.

Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, chairwoman of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah); Macarro, and; Marshall Pierite, chairman and CEO of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana competed for the honorable position.

Given the contentious constitutional amendments on the table, each candidate took a stance on the issue.

Pierite has made it clear that he strongly opposed the amendments.

“We can not pretend that sovereignty is held by only federally recognized tribes. The Tunica-Biloxi Tribe was sovereign long before 1981 and so are the state-recognized tribes that this amendment would disqualify from voting membership,” Pierite said during a comment period on Tuesday. “My heart is very heavy this morning because I feel burdened with all the ancestors that walked before us. The ancestors that sacrificed blood, sweat and tears to get where we are today.”

In an interview with Underscore News and ICT, Pierite called on those in support of the proposed amendments to look at the history of NCAI, and the role the organization has played in helping many nations gain federal recognition.

Andrews-Maltais falls perhaps somewhere in the middle.

When asked about the proposed amendments during a panel discussion at NCAI on Tuesday, Andrews-Maltais appeared to support part of the amendment language while opposing other parts, according to reporting from Indianz.com.

“I would prefer if we at NCAI could move this discussion away from this particular meeting because it is such an important discussion that we need to have and I think that we need to have a deliberate process through which we evaluate what is the intended goal by this action and make sure that we are all on the same page with what the long- and short-term impacts and implications will be, and maybe put a task force together representative of all of these different perspectives to really hash it out and have those difficult conversations because they are hard conversations,” Andrews-Maltais said in an interview with ICT Broadcast.

Sitting on the other end of the spectrum is Macarro, who has expressed support for the proposed amendment.

“NCAI is a Congress, we’re not a trade association per se. As a Congress we’re a deliberative political body advocating the collective interests of sovereign tribal nations to Congress, the administration and the White House,” Macarro said in an interview with ICT Broadcast. “In this circle of sovereigns, there is a rub when at least 24 state and non-federally-recognized tribes sit in parity with sovereign, federally recognized tribal nations.”

Though the two proposed constitutional amendments failed, the issue is likely to come up again with Macarro as president of the organization.

*Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that the Chinook Indian Nation is not a state-recognized tribe. The tribe’s status was incorrect in an earlier version of this story.